The School of Nursing

Graduates of the Jackson P. Burley Practical Nursing Program

Filling a Need

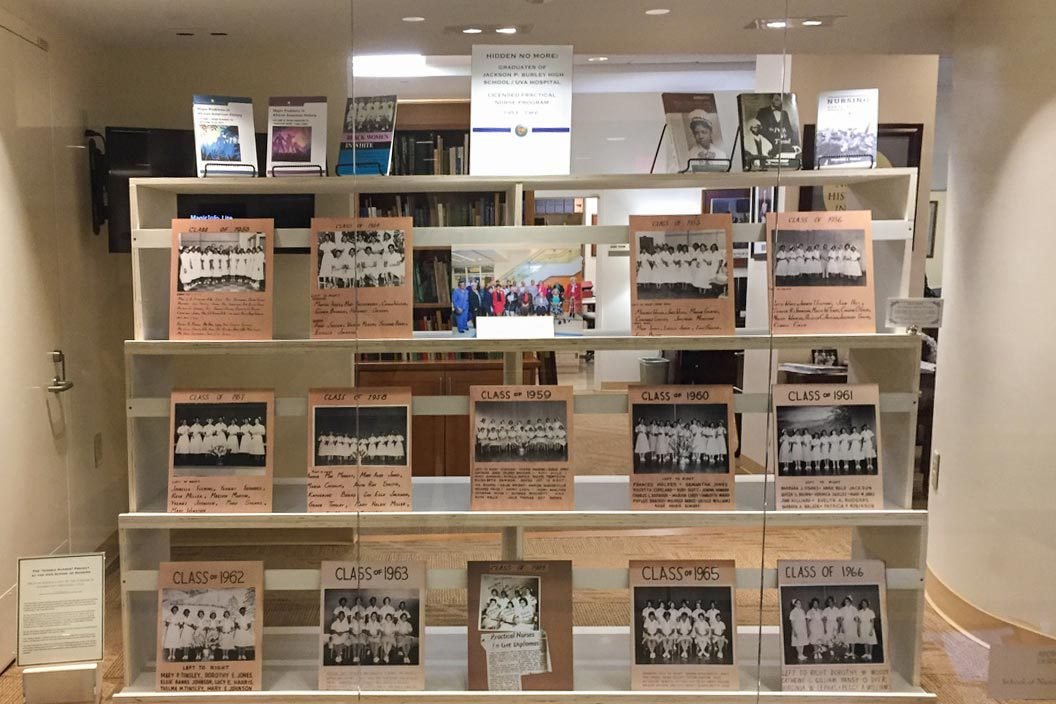

The LPN program, initially a joint venture between the UVA Hospital and Jackson P. Burley High School begun in 1951, was an effort to address a nursing shortage. About 150 African American women (and a few men) were educated in the segregated program. They served alongside white nurses, treated patients of every race, and ran clinics.

Nurses were in short supply after World War II. In the 1950s, however, only white students could attend UVA Hospital’s nursing program and graduate, after three years, with a diploma as registered nurses.

So, Roy Carpenter Beazley (Nurs ’30, ’41), then UVA Hospital’s nursing department director, created a program similar to others across Virginia to quickly train new nurses. In a partnership between UVA and Jackson P. Burley High School, a local school for African Americans, students trained to become licensed practical nurses, completing their education in just 18 months. LPNs typically work under the supervision of registered nurses.

For many black students at the time, it was one of the few options beyond life as a domestic worker. “Had I not gone into nursing, I would have been a nanny,” Walker says. “I felt like I wanted to do a little bit more.”

During the program, students wrapped up their senior year at Burley and then completed their nursing training at the hospital. There, white and black nursing students rarely mixed. McKim Hall, then a dormitory for nursing students, was off-limits to the black nurses in training. But the program provided a monthly living stipend and connected them with local families who rented out rooms.

Their classes also took place away from the white students and in the hospital’s basement. While both groups of nurses treated patients without regard to race, the LPN students were assigned the sickest patients, Walker says.

About 150 students, including a handful of men, completed the Burley program, which ran until 1966. In 1967, UVA launched a bachelor’s program in nursing, following a nationwide trend to move nursing schools out of hospitals and into university programs. Mavis Claytor (Nurs ’70, ’85), the nursing school’s first black student, transferred into UVA from Roanoke College the

next year.

Today, UVA’s School of Nursing boasts a diverse student body, with 39 percent of its current undergraduate and graduate students coming from racial and ethnic minorities and groups underrepresented in nursing, including men.

The LPN graduates always thought of themselves as UVA alumni, says Barbra Mann Wall, director of UVA’s Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry. “The RN nurses got diplomas; the LPNs got certificates,” she says. “They both said, ‘University of Virginia Hospital.’ The diploma nurses have always been considered alumni, but the black nurses weren’t.”

Regardless, those nurses used the program as a steppingstone. Nursing was a respected, high-status job in the local black community. “These black LPNs went on to be activists and leaders in their community,” Wall says.

Outstanding graduates included Charles Barbour (Nurs ’60), Charlottesville’s first black mayor; Grace Tinsley (Nurs ’58), the first black woman to serve on the Charlottesville School Board; and Dr. Anita-Rae Smith-Pankey (Nurs ’58), who later graduated from Howard University medical school and became a psychiatrist.

For Walker, the program launched a long career at UVA Hospital. She was one of the first nurses to work there for 50 consecutive years.

Despite their success at UVA and elsewhere, UVA’s black nurses were largely forgotten by their alma mater. When Walker and Jones discovered the photos at the estate sale a couple of decades ago, they loaned them to nursing school staff. Walker says she’d sometimes look for the pictures on the nursing school walls but didn’t see them. “It stayed in the back of my mind: ‘What happened to them?’”

Turns out the photos were at the school, but forgotten again. It wasn’t until 2018 that staff found them and returned them to Walker. Soon, the staff connected her and Jones with Tori Tucker (Nurs ’12, ’22), a UVA graduate nursing student.

Tucker already knew a bit about the Burley nurses from searching in UVA and state archives during her own research on black nurses and nursing students in Virginia. Her efforts to learn more from the Burley nurses come as part of a project to ensure that the nursing school and its archives cover more than just the history of white nurses. The work is funded with a grant from the Jefferson Trust, an initiative of the Alumni Association.

A special case displayed the pictures that had been stored away for so long. Graduates heard a videotaped address from President James E. Ryan (Law ’92). And they walked across a stage at McLeod Hall Auditorium to receive certificates from then-dean Dorrie Fontaine as the crowd cheered and took photos.

“You studied, trained, and became nurses at a time when African Americans were excluded from our school,” Fontaine told them that afternoon. “This was terribly wrong, and on behalf of the school, I humbly ask you to forgive us for closing our doors to you. It could not have been easy for you during the terrible times of segregation, but you paved the way for so many others to follow in your footsteps.”

Sources:

https://uvamagazine.org/articles/uva_grants_full_alumni_status_to_black_nurses_who_earned_it_decades_ago

https://news.virginia.edu/content/uva-shines-light-recognition-african-american-nurses-it-trained-decades-ago